Getting Off Gas: A How-To Guide to Get Fossil Fuels Out of Your Home

[This piece originally appeared in Canada’s National Observer here.]

This column is a little different from my usual fare. It’s more of a “how-to guide” to decarbonize one’s home. While my writing and public talks generally focus on how to press our governments into emergency mode, ironically, one of the followup questions I am most frequently asked is, “How do I swap my gas furnace for an electric heat pump, and who was your contractor?” So, this one’s for all you folks.

As we seek to confront the climate emergency, retrofitting existing homes and buildings figures centrally in a robust plan. In Canada, the fossil fuels — mainly “natural” gas — we combust in buildings account for about 12 per cent of domestic greenhouse gas emissions (split roughly evenly between residential and non-residential buildings). That doesn’t count the embedded carbon in building construction, the fossil fuels burned to produce electricity in some provinces, or the GHGs associated with extracting and producing the fossil fuels we directly burn in our buildings. In cities, GHGs from buildings generally account for more than half of local emissions.

Discussions about retrofitting our homes often focus on how to enhance energy efficiency — improving insulation, using programmable thermostats, sealing leaks, etc. But here’s the rub: while measures such as these can help reduce emissions and household costs, we can’t achieve carbon-zero as a society by efficiency improvements alone. The only way to get our buildings and homes to carbon-zero is to fuel-swap, meaning, to stop using and combusting fossil fuels in our structures. In particular, we need to stop using “natural” gas (which these days is mostly fracked methane gas) to heat our homes and water and to cook our food. Of all the actions households can take to act on the climate crisis, this shift is one of the most important. Effective now, we need all new buildings to refrain from tying into gas lines. And within the next few years, we need all existing buildings to switch from fossil fuel heat sources to renewable, which in most cases means electricity.

After a process that took about a year, my home is now off fossil fuels. It wasn’t simple or cheap. But it can be done. And in this piece, I share the steps of how my family did it. Some of what we did is specific to B.C., where we live, but much is applicable anywhere. In telling this tale, I’m not trying to virtue signal. Rather, I just want to offer some guidance because people want to know. One of the barriers to climate action is that many of us find it hard to imagine how our homes operate without fossil fuels. So here I offer you a picture of what that can look like.

And let me state from the outset that, without question, a truly successful climate plan requires collective action at the political/policy level (more on that below). Any plan that relies on individual households voluntarily doing what I spell out here will see us fry. Also, I own my home, which provides me with privileges, opportunities and obligations to act that do not exist for most renters. Ultimately, however, a comprehensive climate program does require that all our homes cease using fossil fuels. So this article walks you through how that can be done.

Where we started from

A couple years ago, my family’s home — a 12-year-old, 1,400-square-foot, well-insulated duplex in East Vancouver — was heated with a high-efficiency gas boiler. The boiler produced hot water for both our direct water needs and for pipes that provided lovely radiant heated floors in the winter. We also had a gas fireplace in the living room we rarely used, and we cooked on a gas stove.

We paid BC Hydro an average of just under $80 a month for our electricity use, which varied little throughout the year, and we paid FortisBC for our gas use. Our monthly gas bill was about $50, ranging from a low of about $20 in the summer to a high of about $85 in the winter.

From the get-go, driven by concern for the climate emergency, we knew we wanted to get the gas out of our home. We also welcomed the idea of getting gas fumes out of our living spaces and the health and safety benefits that would result for us and our kids. We knew the main recommendation was to switch to an electric-powered heat pump system, but what kind?

First, it’s useful to explain what a heat pump is. Many people confuse it with a geothermal system, which pulls heat from deep underground with pipes. A heat pump isn’t an underground system. It’s usually a single outdoor unit about 3x2.5x1 feet with a large fan (see photo below), which extracts heat from the ambient air (yes, even in winter), and then pipes that heat indoors, either taking that heat to a central duct system or to wall-mounted units about the size of an air conditioner in each room. BC Hydro has a nice short video explaining how a heat pump works here. The added benefit is that in the summer, the same system operates in reverse, extracting heat out of your home and carrying cool air in.

In many respects, the term “heat pump” is a misnomer; it would more accurately be named an “air comforting” system, or a “heat and cooling” pump.

Heat pumps are dramatically more efficient (and therefore less expensive to operate) than conventional baseboard electric heating systems. That’s because the heat pump isn’t generating heat, but rather, extracting and moving heat — way easier!

Our conversion journey started by consulting with a few experts I know, collecting advice about what kind of heat pump system would work best for us. (This might have been overkill; for most people, this wouldn’t be necessary, but I knew I wanted to be able to explain what we were doing and why.) We considered an air-to-water heat pump that would allow us to keep our radiant floors, but few contractors were familiar with these systems. Further, such a system, at least in our home, looked unlikely to deliver summer cooling particularly well. So in the end, we decided to abandon our radiant floors and went with a more typical air-to-air system described above.

Next, we collected quotes from about six contractors and were ready to go.

What we did

First thing we did — anticipating the electrification process risked substantially ramping up our monthly electric bills — we contracted with a local solar company, Solar Connect, and installed a bank of 14 panels on our garage roof in the summer of 2019. Solar panels aren’t cheap, but the cost is coming down, and ours will pay for themselves in lower monthly electricity bills at least three times over the course of their working lives. BC Hydro offers a simple net metering program, whereby any electricity we produce in excess of our monthly needs is credited to our BC Hydro account. In the peak of summer, we are producing more electricity than we consume and accumulating a modest credit, which we draw down in the winter.

Given that British Columbia’s electricity system is hydro-based, the solar panels don’t directly lower GHGs in our province (in provinces still using coal and/or gas generated electricity, the solar panels would indeed help to lower GHGs). However, in addition to keeping our monthly electric bill in check, the solar panels mean we are providing a public benefit; even after fuel-swapping our home, we have not significantly increased our draw on the BC Hydro system. Were many homes and buildings to do this, it would save the public utility from needing to undertake huge new investments in new electricity production capacity. That said, this step was not necessary to get the gas out of our homes, so consider it an extra.

Second, we took out the gas stove and replaced it with a new induction electric stove. I know there are many of you who swear by the joys of cooking with gas. To which I say — you should try induction electric. As many chefs will tell you, they’re fabulous! Induction stoves are nothing like the old coil electrics. Like gas, they instantly provide heat, and at just the desired level. And they are safer than old electric or gas stoves because induction operates by magnetic connection between the stove surface and the bottom of a pot or frying pan. Once a pot is removed, it instantly cools, dramatically lowering risks of fire or injury. And no more breathing gas fumes.

Next, in May 2020, the heat pump system was installed by local contractor Ashton Plumbing and Heating, a process that took only a couple days. The inside gas lines were sealed shut. Our gas boiler and accompanying hot water tank were removed, replaced by a Mitsubishi 4-zone heat pump system (with one wall-mounted unit downstairs and one in each of three bedrooms upstairs.) The external unit is very quiet, and four pipes carry the hot or cold air from that main unit to the wall-mounted units indoors. (The pipes are very discrete, running along one back external wall and then through the attic to reach the two farthest units.)

Seth on the right, with son Aaron and wife, Vancouver city councillor Christine Boyle, pose with the external heat pump. Photo by David Bishop, Bring it Home 4 The Climate

Single wall-mounted unit delivers heat and cooling to our whole downstairs floor.

At the same time, we installed a conventional electric hot water heater (there are also heat pump options for hot water, but we don’t go that route).

The final reno: we ripped out the gas fireplace and replaced it with some beautiful built-in bookshelves that we like much better.

With all that done, the last — and deeply satisfying — act: we shut off the gas line to our home and cancelled our FortisBC account.

Ron Sim of Ashton Heating shuts off our gas line.

The costs and benefits

So, what did it all cost? Here’s the breakdown of the elements needed to get the gas out of our home:

· Induction electric stove: $2,000 plus tax

· Electric hot water heater and tank, including installation: $3,400 plus tax

· Heat pump system, including installation: $17,000 plus tax (minus $9,000 in rebates)

The price of the heat pump may elicit some sticker shock. But, both the BC government and the City of Vancouver now provide rebates for homes converting from gas to electric systems. At the time we did our fuel swap, those rebates amounted to $3,000 and $6,000 respectively, bringing the net cost of the heat pump down to $8,000. The province has since sweetened the pot with a further $3,000 in rebates, so today, the net cost would have been $5,000. And consider that in five years or so, it probably would have been time to replace the boiler regardless, the cost of which would approach that net heat pump price.

With respect to monthly operating costs...

The operating cost of the electric hot water heater has been negligible (we wash clothes in cold water and generally hand wash the dishes). Nor did I notice an increase when we switched from the gas stove to induction electric.

It’s really only been at the peak of winter that we saw a notable jump in our electric bill; with our solar panels delivering only modest power in the darker winter months and the heat pump operating all day, our electricity draw certainly went up. Comparing our winter BC Hydro bills from before and after the switch, minus what we used to pay in gas, the costs seem to be up $10 to $20 a month.

Overall, however, in the first full year since the swap, our Hydro bill averaged $105 a month, about $25 more than before this journey began. But we no longer have a Fortis gas bill of ~$50 a month, so on net, we are spending about $25 less in monthly utility costs, even with the addition of summer air conditioning, but helped by the solar panels. We also charge our electric car on that bill (although we don’t drive much, so those costs are minimal).

Over time, the cost advantage of electricity over gas will likely increase as the escalating carbon price over the next 10 years hikes the cost of gas (although, on the flip side, we also need our governments to be smart about their electricity development plans, so as not to drive up electricity costs and perversely discourage fuel-swapping off fossil fuels).

No doubt this conversion has also increased the value of our home, as future owners will not face the inevitable need to fuel swap down the road once robust climate policies are in place, and they will benefit from the upfront capital costs we assumed for the solar panels and heat pump.

And the greatest benefit — we’ve eliminated GHG emissions from our home, cancelled our account with FortisBC, and the system works wonderfully! We have cosy heat in the winter (no need for a back-up heat source in coastal B.C.). And the cooling in the summer — a benefit to which we paid little heed at the start of this process — is incredibly effective; during last summer’s deadly heat dome, our home remained very comfortable, and numerous friends and family ended up visiting for a few hours of respite to escape the record temperatures.

Also, our kids seem proud of the new system and like showing it to visitors, and, well, that’s worth a lot.

No substitute for collective action

As stated upfront, the path to victory on the climate emergency will not be won by encouraging and incentivizing households to voluntarily do what we did. While individual households all have their part to play, confronting the climate crisis requires collective and state-led action. As my family’s conversion journey makes clear, the process can be complicated and it is costly, and if we are hoping everyone will do this on their own, we’re going to lose the climate fight.

Why is there no escaping government action?

First, there is little point converting our homes and vehicles to electricity if that electricity is produced by burning fossil fuels like coal or gas. I live in B.C., which thankfully means the electricity is generated virtually entirely from renewable power. But that's not yet true in most jurisdictions. Making that reality a widespread one isn’t something any of us can achieve on our own, but only by collectively demanding such changes to our electricity infrastructure.

Second, we need to make switching to electric heat pumps simpler and much more affordable, especially for lower-income families. Government rebates help, but not enough. What if we had a new Crown corporation (or a subsidiary of BC Hydro) or a public enterprise of some sort that was mass producing GHG-free electric heat pumps and employing an army of installers? With the profit margins removed and the gains that come from economies of scale, the price of the heat pumps would come down. And the installers could come to our homes and simplify the process, giving us clear advice without each of us having to wonder which contractor was taking the least advantage of us.

Third, public financing innovations would also help with the upfront capital costs. Most people don’t have the cash on hand for these purchases. Also, one factor discouraging the purchase of solar panels and heat pumps is some people worry that if they end up selling their home within a few years, a future owner will realize most of the cost savings of these investments. Imagine if, instead, financing for these large purchases were provided by public utilities like BC Hydro, and loans were carried and paid back over time on one’s monthly utility bill. Meaning, the capital cost and loans would stay with the building, not the original purchaser, as the benefits flow to whomever owns the home at the time.

Under any future scenario, as we confront the climate crisis, energy costs are going up, and thus, issues of energy poverty and cost stress for lower and middle income households is an issue that needs to be mitigated. And that’s something we can only do together.

Finally, while all this encouragement and financial assistance is needed (policy carrots), fuel swapping can’t be left to voluntary goodwill. We also need the state to set clear near-term dates by which fuel-swapping will be mandatory (the policy sticks). Tackling the climate crisis and eliminating GHGs from our homes isn’t optional. We need to get this done.

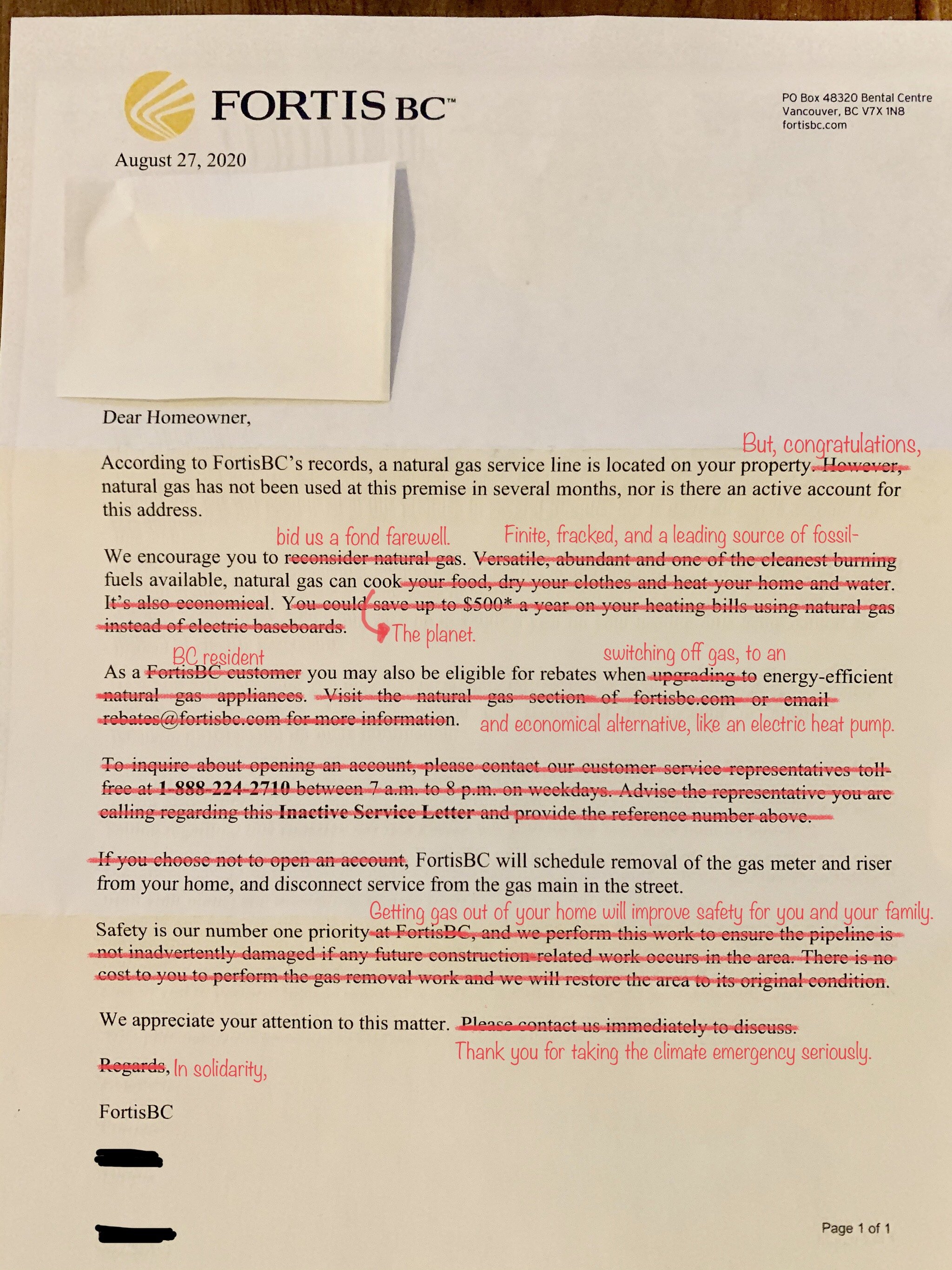

Postscript: Three months after cancelling our gas account, we received this letter from FortisBC. Well, the red ink text we added in an irate effort to “fix” the letter and share it — widely — on social media. Governments need to crack down on insidious efforts like this by the gas companies to discourage electrification efforts, as I outlined in this previous column. Gas companies like FortisBC are regulated monopolies, and as such, should not be allowed to block progress on the task of our lives.

Our marked up the letter from Fortis urging us to go back to gas